Introduction – the model dilemma

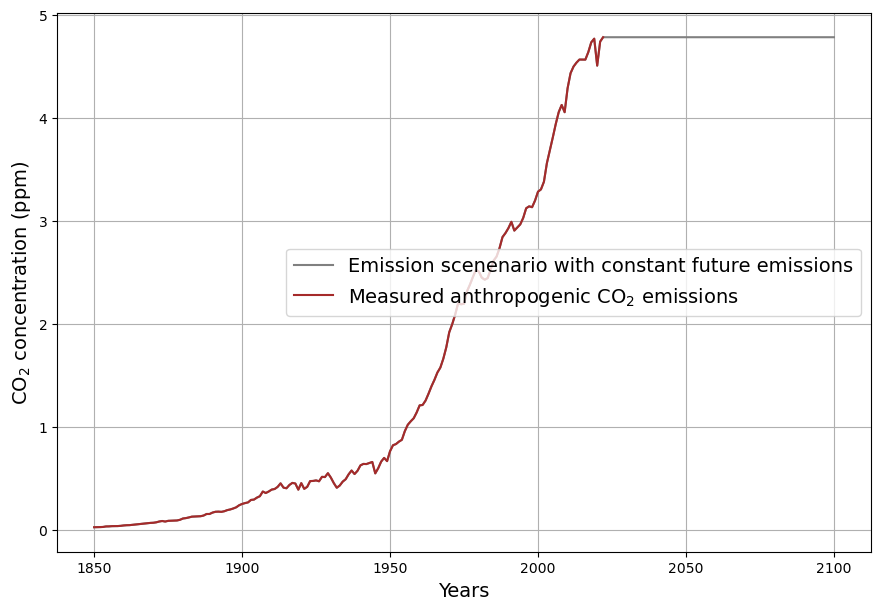

There is broad consensus that the increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations since 1850 is due to the sharp rise in anthropogenic CO2 emissions since that time. Anthropogenic emissions have remained constant within the margin of measurement accuracy for around 10 years, and no major deviation from this trend is expected in the future. For illustrative purposes, constant emissions are assumed for the future scenario, based on the IEA’s Stated Policy Scenario. This debatable assumption is irrelevant for the actual calculation, as it is based exclusively on measurements of past data. The measured emissions and the assumed future emissions scenario are shown in Fig. 1. The use of the somewhat unusual unit of measurement ppm for emissions is due to the need to compare emissions and concentration ((1 ppm = 2.123 Gt C = 7.8 Gt CO2).

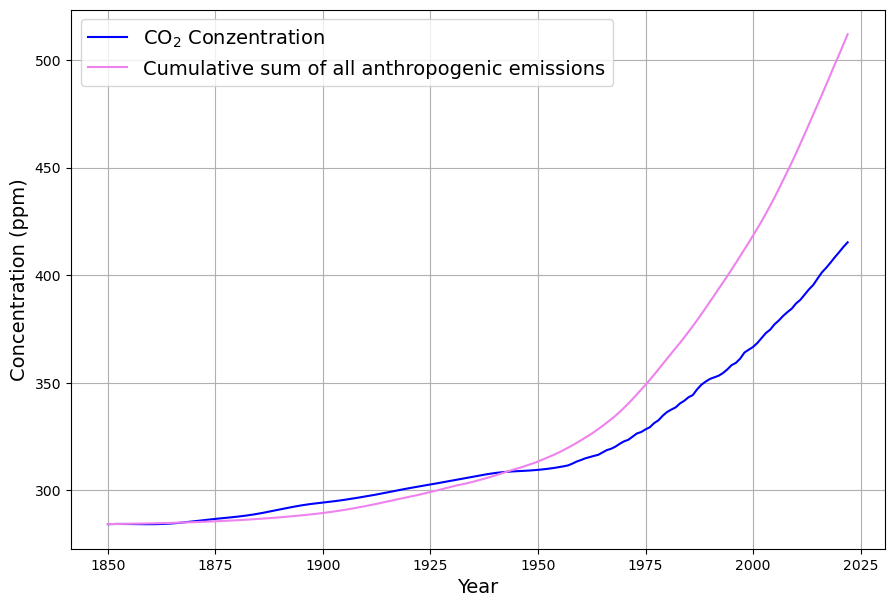

Anthropogenic emissions do not remain entirely in the atmosphere. Their concentration has so far grown only about half as fast as it would have if all anthropogenic emissions had remained in the atmosphere, as shown in Fig. 2. This correlation has been valid since around 1950, when the phase of strongest emission growth of about 4% per year began, which continued until the mid-1970s.

The somewhat strange circumstance that between 1875 and 1945 the actual concentration is greater than the hypothetical concentration, in which all anthropogenic emissions remain in the atmosphere, is probably due to the fact that the significantly high emissions in the first half of the 20th century due to land use changes were not taken into account here. This also plays only a very limited role in the calculations made here, because only data after 1960 is used to calculate the result.

The reduced increase in concentration compared to anthropogenic emissions is due to the two major sink systems, land plants and the world’s oceans, both of which absorb considerable amounts of CO2. The important question is what this absorption depends on, and more importantly, how the strength of absorption will develop in the future. This is reflected in the various sink models. Of the many variations of these models, two important, fundamentally different representatives are currently being investigated:

- the linear sink model, in which the sink effect is a strictly linear function of CO2 concentration,

- the Bern model, which assumes that about 20% of emissions remain in the atmosphere for a very long time.

Which of the models is correct has serious implications for how we deal with CO2. If some of it remains in the atmosphere virtually forever, this ultimately implies the need to reduce anthropogenic emissions to zero, i.e., budgeting, which is currently the political goal in Germany and the EU. If, on the other hand, the linear model is correct, we could rely on the fact that as concentrations rise, more CO2 will be absorbed and the Paris climate target of balancing CO2 sources and sinks will be achieved in the second half of this century, even if emission patterns remain largely unchanged.

This article therefore focuses on finding a criterion to prove the correctness of one or the other model using existing measurement data.

What are sinks? A formal description

First, the measurable sink effect ![]() of year

of year ![]() is determined as a result of the conservation of the total atmospheric mass of CO2 using the continuity equation. The increase in concentration

is determined as a result of the conservation of the total atmospheric mass of CO2 using the continuity equation. The increase in concentration ![]() in the atmosphere is calculated as the difference between all emissions, i.e., anthropogenic emissions

in the atmosphere is calculated as the difference between all emissions, i.e., anthropogenic emissions ![]() and natural emissions

and natural emissions ![]() , and total absorption

, and total absorption ![]() :

:

![]() (Equation 1)

(Equation 1)

The global sink effect ![]() is the part of anthropogenic emissions

is the part of anthropogenic emissions ![]() that does not contribute to the increase in concentration

that does not contribute to the increase in concentration ![]() :

:

![]() (Equation 2)

(Equation 2)

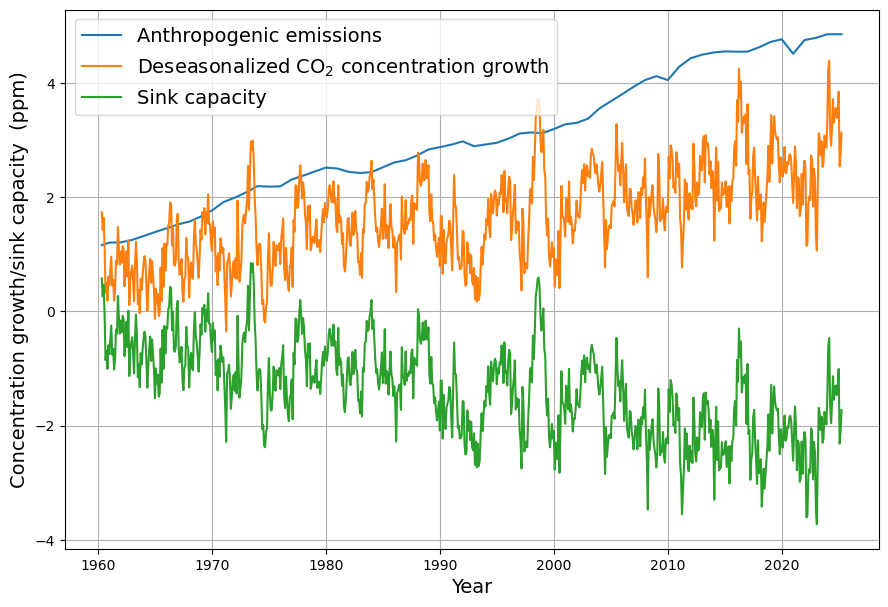

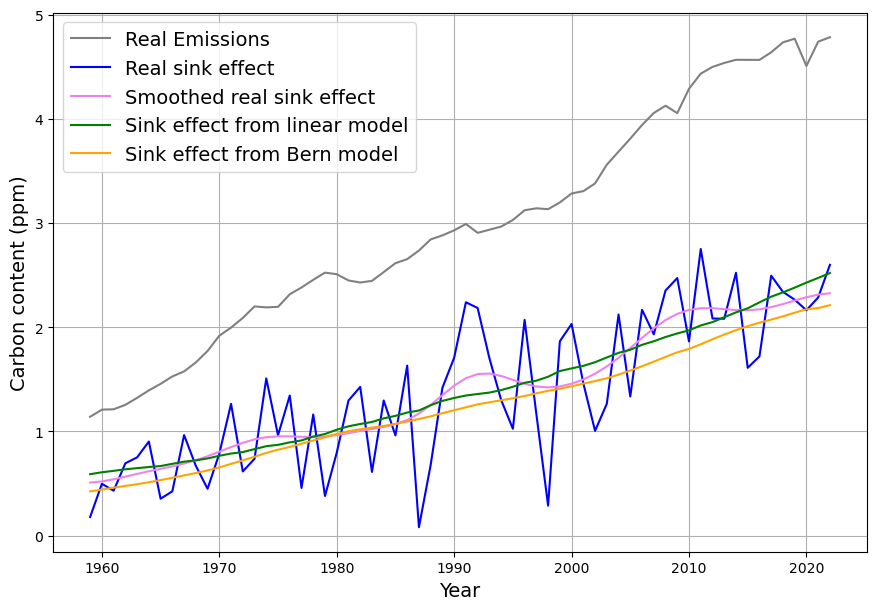

This sink effect can be determined from the available emission and CO2 concentration data (monthly concentration data from Mauna Loa) without modeling and is shown in Figure 3 as a time series from 1960 onwards. The data on the monthly measured concentration increase are seasonally adjusted by determining the difference from the same month of the previous year. Emissions and concentration are measured in the same unit of measurement ppm (1 ppm = 2.123 Gt C = 7.8 Gt CO2).

Consequently, the sink effect is also the difference between absorptions ![]() and natural emissions

and natural emissions ![]()

![]() (Equation 3)

(Equation 3)

It also follows that emissions from land use changes, which are subject to considerable uncertainty, are calculated as belonging to the unknown natural emissions.

The global sink effect defined in this way can be easily measured. Therefore, a method is sought to evaluate the respective sink model using the measured sink effect. The aim of this study is not to evaluate the correctness of the respective models based on their assumed causal mechanisms, but solely to find a mathematical statistical criterion for deciding, on the basis of measurement data, which model better corresponds to reality1.

The two sink models

The linear sink model

Two sink models are compared. One, the “linear sink model” or “bathtub model,” assumes that the sink effect in year ![]() ,

, ![]() , increases strictly linearly with the CO₂ concentration (of the previous year)

, increases strictly linearly with the CO₂ concentration (of the previous year) ![]() (a more detailed analysis shows that the expected value of the time difference between concentration and sink effect is approximately 15-18 months):

(a more detailed analysis shows that the expected value of the time difference between concentration and sink effect is approximately 15-18 months):

![]() (Equation 4)

(Equation 4)

where ![]() represents the assumed pre-industrial equilibrium concentration without anthropogenic emissions.

represents the assumed pre-industrial equilibrium concentration without anthropogenic emissions.

The data for the period 1960-2025 yield the following estimates:

![]() C^0

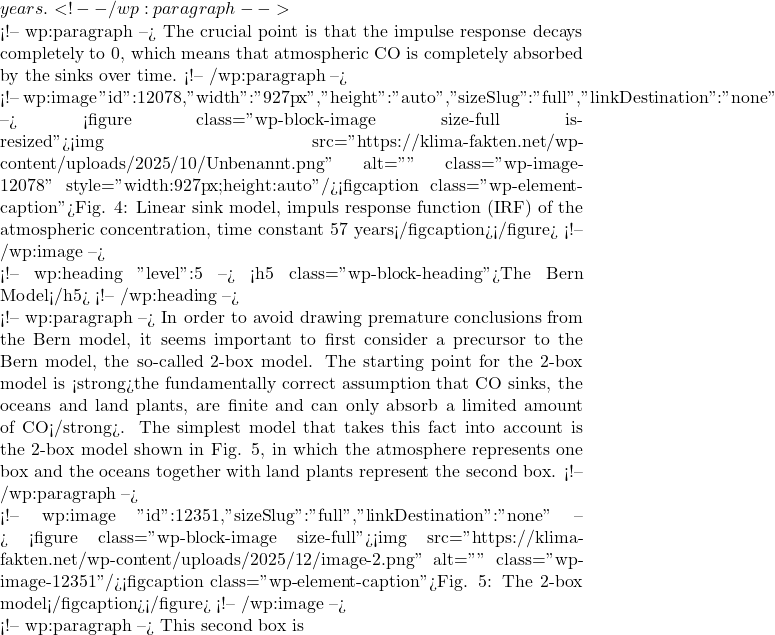

C^0 IRF^{linear}(t)=e^{-\frac{t}{\tau}}

IRF^{linear}(t)=e^{-\frac{t}{\tau}}![]() \tau=1/a\approx 57

\tau=1/a\approx 57  k

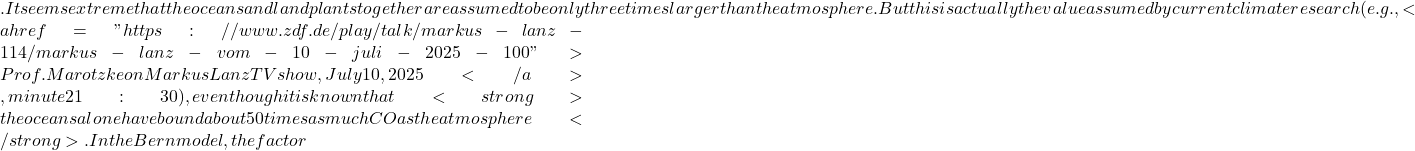

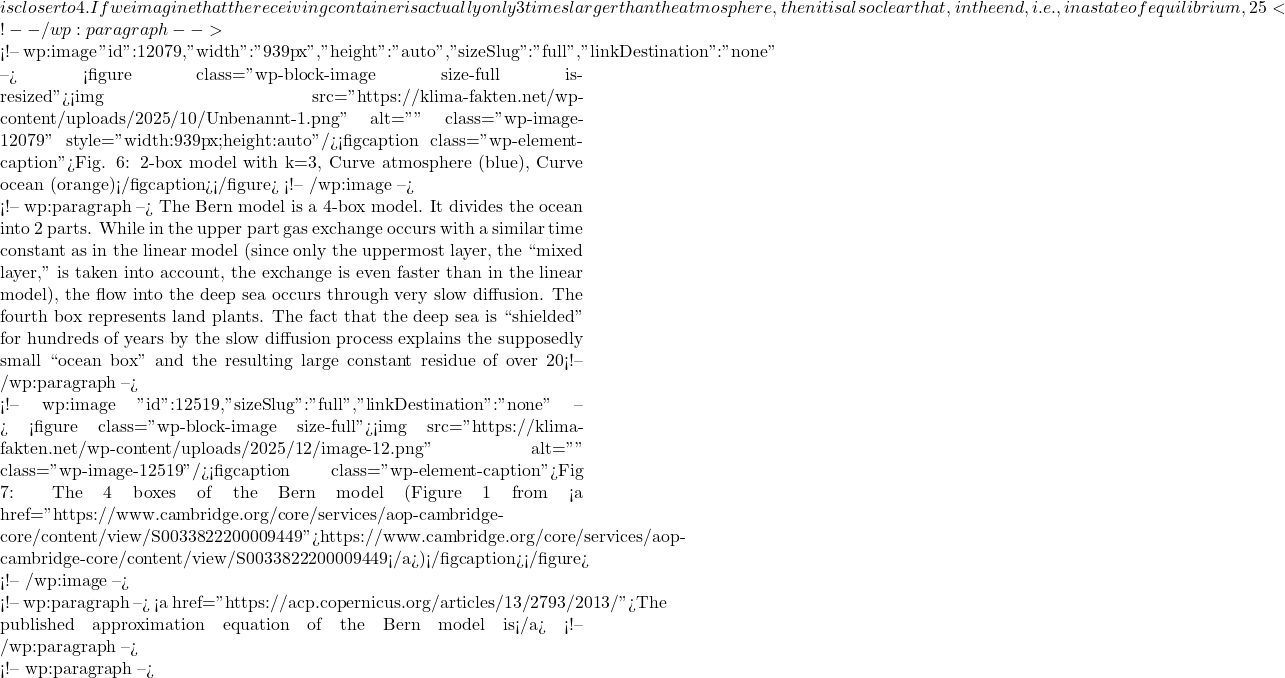

k![]() k=3

k=3 k

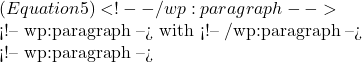

k IRF^{Bern}(t) =a_0 + \sum_{i=1}^3 a_i\cdot e^{-\frac{t}{\tau_i}}

IRF^{Bern}(t) =a_0 + \sum_{i=1}^3 a_i\cdot e^{-\frac{t}{\tau_i}} a_0=0.21787, a_1=0.22896, a_2=0.28454, a_3=0.26863

a_0=0.21787, a_1=0.22896, a_2=0.28454, a_3=0.26863![]() \tau_1=381.33, \tau_2=34.785, \tau_3=4.1237

\tau_1=381.33, \tau_2=34.785, \tau_3=4.1237 a

a![]() a_i

a_i![]() S_i = a_i\cdot(C_{i-1} – C^0)

S_i = a_i\cdot(C_{i-1} – C^0)![]() a_i

a_i![]() S_i

S_i C^0

C^0![]() a_i = \frac{S_i}{C_{i-1}-C^0} = \frac{E_i – (C_i – C_{i-1})}{C_{i-1}-C^0}

a_i = \frac{S_i}{C_{i-1}-C^0} = \frac{E_i – (C_i – C_{i-1})}{C_{i-1}-C^0}![]() a_i

a_i![]() C_i

C_i![]() C^0

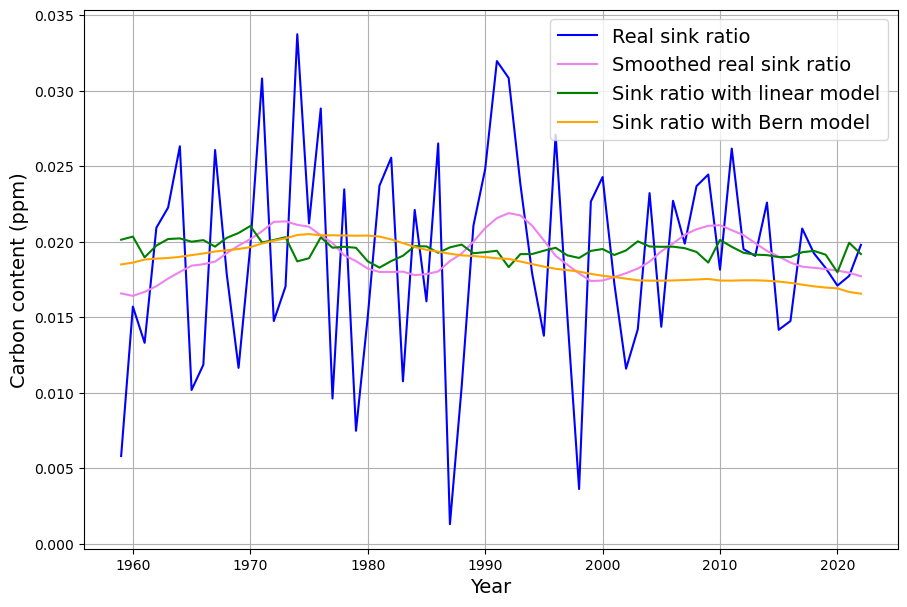

C^0![]() a_i$ for the linear model (green) and the Bern model (orange).

a_i$ for the linear model (green) and the Bern model (orange).

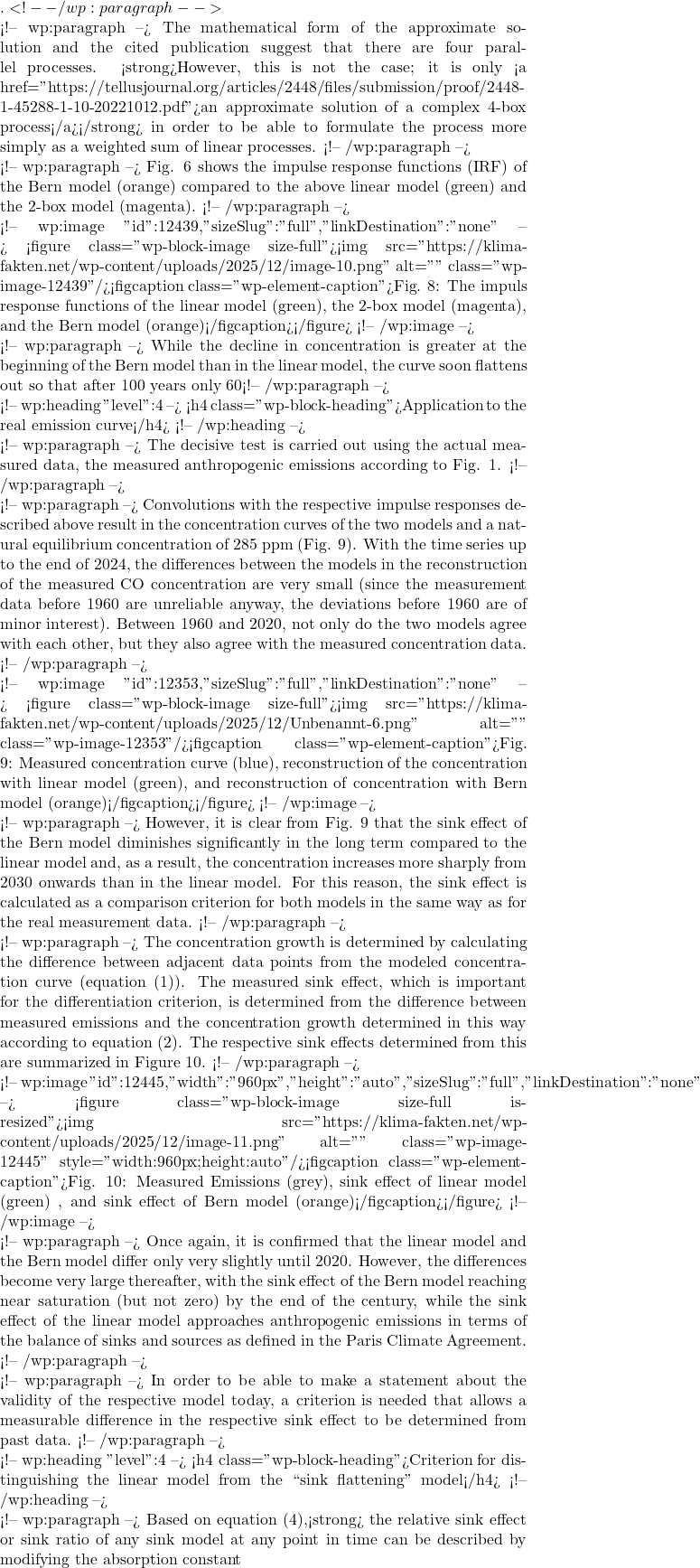

After a slight increase in the relative sink effect during the phase of exponential emissions growth until 1975, the Bern model shows a significant decline in the relative sink effect from 1980 onwards, while the relative sink effect in the linear model remains largely constant, as expected.

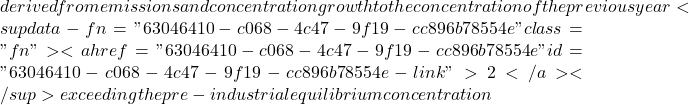

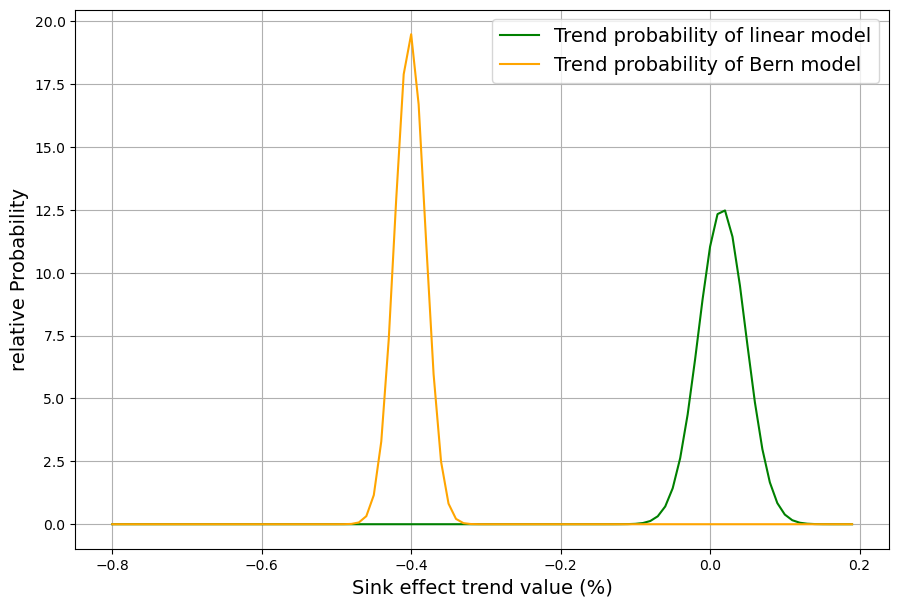

In order to obtain statistically evaluable measurement data from this graphical illustration using past data, the course of the relative sink effect over the 42-year period from 1980 to 2022 is approximated with a straight line in each case (Fig. 12):

The trend of the two curves is well represented by the slope of the straight lines. The slope of these straight lines is therefore the significant distinguishing criterion between the two models. The least squares estimate of the straight line equation also gives the standard error of the slope. These two measured values are now plotted with their error distributions in a diagram (Fig. 13). In order to obtain a dimensionless result, the quotient of the slope and the expected value at the midpoint of the period is plotted and used as the relative slope (in %) as a value on the X-axis of Fig. 13. The diagram shows the probability distributions for the relative slope of both models.

The two probability distributions are so clearly disjoint that this provides a criterion in which the two models differ greatly, even over the last 40 years. In plain language, this means that there are hardly any trend deviations from the sink ratio of 0 in the linear model, while in the Bern model, there has been a trend since 1980 toward a relative reduction in the sink ratio of 0.4% per year, starting from a value that was still greater than in the linear model in 1980 but is already considerably lower now, as can be seen in Fig. 12.

The crucial question now, of course, is how the actual measured data behaves with regard to this criterion, and thus which of the two models is more consistent with the real data.

The sink ratio of the measured data

The decisive test is carried out with the actual measured data. With the time series up to the end of 2024, as shown in Fig. 9, the differences between the models in the reconstruction of the measured CO2 concentration are very small.

For this reason, the more meaningful curves of the measured sink effect are considered. In fact, slight differences are already apparent today. Since the measured sink effect (blue) is subject to extremely strong short-term fluctuations, these are smoothed (purple). This operation does not distort the long-term trend. For comparison, Fig. 14 shows the measured sink effect as annual “raw data” and as its smoothed curve in comparison to the linear and Berner models.

The model values of both models are still within the large statistical fluctuations of the measured sink effect as individual values. However, there are very slight differences in trends.

This is only clearly visible in the representation of the sink ratio or the relative sink effect in Fig. 15:

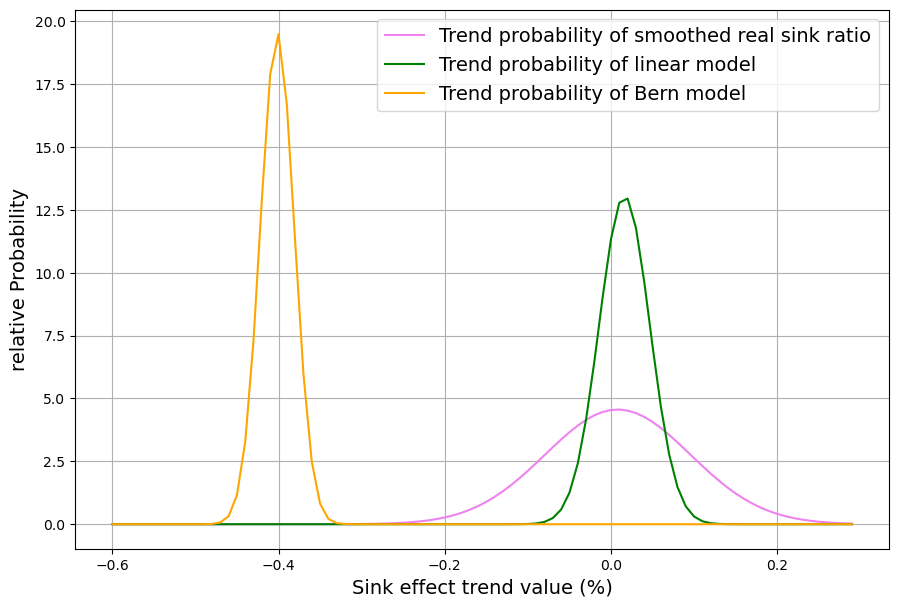

The sink ratio of the smoothed measured sink effect is approximated for the period 1980-2022 by a straight line whose slope is calculated with standard error and entered into a joint diagram (Fig. 16) with the results of the two models.

The result is unambiguous. Only the linear sink model is compatible with the measured sink effect of the last four decades. Contrary to superficial appearances, the decline in the relative sink effect of the Bern model, which began in 1980, cannot be reconciled with the measured values. Accordingly, the Bern model is not compatible with reality.

The same applies to other models such as the budget model (where the deviation from reality is even greater than with the Bern model) and the 2-box model described above. Only the linear sink model can be reconciled with the real data from the last 45 years. A 2-box model in which the second box is not 3 times but, for example, 50 times larger than the first was not investigated. It is to be expected that such “almost linear” models are also compatible with the measured data.

Fußnoten

- “It doesn’t matter how beautiful your theory is, it doesn’t matter how smart you are. If it doesn’t agree with experiment, it’s wrong.” (Richard Feynman) ↩︎

- This is a simplification, in der publikation Evaluating the Effectiveness of Natural Carbon Sinks Through a Temperature-Dependent Model the expected value of the time lag is calculated as 15-18 months ↩︎